Go To Section

London

County

Available from Boydell and Brewer

Elections

| Date | Candidate |

|---|---|

| 1386 | Aldermen |

| John Hadley | |

| John Organ | |

| Commoners | |

| Adam Carlisle | |

| Thomas Girdler | |

| 1388 (Feb.) | Aldermen |

| William More I | |

| John Shadworth | |

| Commoners | |

| William Baret | |

| John Walcote | |

| 1388 (Sept.) | Aldermen |

| Adam Bamme | |

| Henry Vanner | |

| Commoners | |

| William Tong | |

| John Clenhand | |

| 1390 (Jan.) | Aldermen |

| William More I | |

| John Shadworth | |

| Commoners | |

| Adam Carlisle | |

| William Brampton I | |

| 1390 (Nov.) | Aldermen |

| John Hadley | |

| William More I 1 | |

| Commoners | |

| Thomas Newton | |

| John Bosham | |

| 1391 | Aldermen |

| William Sheringham | |

| William Brampton I | |

| Commoners | |

| William Standon | |

| John Walcote | |

| 1393 | |

| 1394 | Aldermen |

| William Standon | |

| John Frosh | |

| Commoners | |

| Thomas Exton | |

| John Wade I 2 | |

| 1395 | Aldermen |

| Adam Carlisle | |

| Drew Barantyn | |

| Commoners | |

| Geoffrey Waldern | |

| William Askham | |

| 1397 (Jan.) | Aldermen |

| William Standon | |

| William Brampton I | |

| Commoners | |

| William Hyde I | |

| Hugh Short | |

| 1397 (Sept.) | Aldermen |

| Andrew Newport | |

| Drew Barantyn | |

| Commoners | |

| Robert Ashcombe | |

| William Chichele | |

| 1399 | Aldermen |

| John Shadworth | |

| William Brampton I | |

| Commoners | |

| William Sunningwell | |

| Richard Marlow | |

| 1401 | |

| 1402 | Aldermen |

| John Hadley | |

| William Parker I | |

| Commoners | |

| John Prophet II | |

| William Norton II 3 | |

| 1404 (Jan.) | Aldermen |

| William Standon | |

| Drew Barantyn | |

| Commoners | |

| William Marchford | |

| John Prophet II 4 | |

| 1404 (Oct.) | Aldermen |

| John Woodcock | |

| William Brampton I | |

| Commoners | |

| Alan Everard | |

| Robert Haxton 5 | |

| 1406 | Aldermen |

| William Standon | |

| Nicholas Wotton | |

| Commoners | |

| John Sudbury | |

| Hugh Ryebread | |

| 1407 | Aldermen |

| William Askham | |

| William Cromer | |

| Commoners | |

| William Marchford | |

| John Bryan | |

| 1410 | Aldermen |

| Drew Barantyn | |

| Henry Halton | |

| Commoners | |

| John Reynwell | |

| Walter Gawtron 6 | |

| 1411 | Aldermen |

| Richard Marlow | |

| Thomas Fauconer | |

| Commoners | |

| John Sutton II | |

| John Mitchell 7 | |

| 1413 (Feb.) | Aldermen |

| Drew Barantyn | |

| William Askham | |

| Commoners | |

| William Marchford | |

| Walter Gawtron 8 | |

| 1413 (May) | Aldermen |

| Drew Barantyn | |

| William Askham | |

| Commoners | |

| William Marchford | |

| Walter Gawtron | |

| 1414 (Apr.) | Aldermen |

| Richard Marlow | |

| Robert Chichele | |

| Commoners | |

| William Burton I | |

| Alan Everard 9 | |

| 1414 (Nov.) | Aldermen |

| William Waldern | |

| Nicholas Wotton | |

| Commoners | |

| William Oliver | |

| John Gedney | |

| 1415 | Aldermen |

| Robert Chichele | |

| William Waldern | |

| Commoners | |

| John Reynwell | |

| William Mitchell | |

| 1416 (Mar.) | Aldermen |

| Richard Marlow | |

| Thomas Fauconer | |

| Commoners | |

| William Weston IV | |

| Nicholas James 10 | |

| 1416 (Oct.) | Aldermen |

| Richard Whittington | |

| Thomas Knolles | |

| Commoners | |

| John Perneys | |

| Robert Whittingham 11 | |

| 1417 | Aldermen |

| William Cromer | |

| William Sevenoak | |

| Commoners | |

| John Welles III | |

| John Butler II | |

| 1419 | Aldermen |

| Nicholas Wotton | |

| Henry Barton | |

| Commoners | |

| Richard Meryvale | |

| Simon Sewall | |

| 1420 | Aldermen |

| Thomas Fauconer | |

| John Mitchell | |

| Commoners | |

| Solomon Oxney | |

| John Higham | |

| 1421 (May) | Aldermen |

| William Waldern | |

| William Cromer | |

| Commoners | |

| William Burton I | |

| Richard Goslyn | |

| 1421 (Dec.) | Aldermen |

| Thomas Fauconer | |

| Nicholas Wotton | |

| Commoners | |

| John Whatley | |

| John Brockley |

Main Article

Although the population of London numbered at least 40,000 during the late 14th century, only the freemen, a far smaller group comprising about one quarter of the adult male residents, played any part in civic affairs. They alone were enfranchised, having undertaken in return to pay taxes and bear whatever corporate responsibilities fell upon them as citizens. In our period freedom came most usually through patrimony or apprenticeship, but it could also be bought and, in certain cases, was a perquisite of office. In theory, the same rights, privileges and opportunities were available to every citizen once he had sworn an oath of loyalty to the government of London. In practice, however, a fairly narrow oligarchy of wealthy merchants enjoyed a virtual monopoly of high office, which they defended staunchly against attack. Despite his initial success, the radical mayor, John of Northampton†, failed to restrict the powers of the great mercantile guilds; far from helping the artisans and tradespeople of London to assert their political rights, his extremism provoked so violent a reaction that for many years after his fall (in 1384) the idea of reform was dismissed out of hand.12

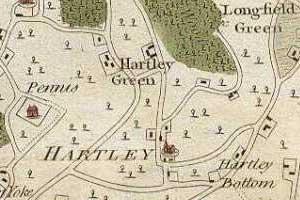

During the later Middle Ages London was divided first into 24, and then after 1394 into 25, wards, which were the basic units of administration and law-enforcement. Every male householder and servant had to attend the annual wardmote (or meeting), although the freemen alone were entitled to elect their aldermen and common councillors. Initially the people of London used the ancient court of husting as a general assembly where matters of civic importance could be debated, but by the late 14th century this function had been assumed by the common council, a more formal and selective body. Throughout our period it had 96 members, chosen as representatives of their several wards (although for a short time in the 1380s the right of election passed to the London guilds). The common council met at least once a quarter at the Guildhall and dealt with a wide variety of business, most notably the numerous inquiries and supervisory tasks delegated to small ad hoc internal committees. It was summoned by the court of aldermen, the most powerful single institution in medieval London, which assumed overall responsibility for almost every facet of civic government.

The office of alderman brought with it a heavy burden of duties and often proved a financial drain on the occupant, although many were prepared to accept these disadvantages in return for the status which aldermanic rank bestowed. Others were less public spirited, however, and had to be sharply reminded of their civic obligations. John Gedney, the prosperous draper who, in 1415, refused to take up the office of alderman to which he had been elected, was imprisoned and threatened with the confiscation of all his goods should he remain obdurate. One year later the court of aldermen decreed that anyone who attempted to evade their responsibilities by disrupting the elections would be fined £5.13 The great majority of aldermen came from the most powerful city companies and generally held office for life, subject only to removal for misconduct. John of Northampton and his fellow reformers had tried to democratize the system by forcing each alderman to retire after one year’s service, but their opponents subsequently made re-election possible, and in 1394 even this restriction was formally abolished on the authority of Parliament. The court of aldermen was further able to maintain its exclusivity through a system of double elections introduced in 1397. Whereas, before, each alderman had been chosen directly at the wardmote, from this date onwards the names of at least two (and from 1402 four) ‘reputable and discreet men’ were submitted to the court, which made the final choice.14

Under these circumstances the aldermen had little to fear from the radical element in London society, although on the whole their rule was accepted as just and equitable, if somewhat reactionary. The court of aldermen was answerable to the Crown for the enforcement of law and order and the administration of justice in the City, and fearing that any signs of laxity on its part might lead to the withdrawal of these privileges, it proved a rather harsh and repressive body. The penalties for questioning the established order or insulting an office-holder were particularly severe. In 1387, for example, William Highlot was sentenced to lose his right hand for insulting one alderman, and shortly afterwards a London butcher faced the prospect of six months’ imprisonment and a humiliating penance for his rudeness towards another. Both miscreants were eventually pardoned, but not until they had offered substantial sureties for their good behaviour in the future.15 The court also undertook to supervise the administration of city property and the upkeep of London Bridge. In the former task it was assisted by a chamberlain and in the latter by two bridge wardens, the accounts of all three being audited annually by a committee of aldermen and commoners. A considerable part of the court’s time was taken up with the direction of commercial and mercantile affairs in the City. Besides dealing with disputes between merchants and tradespeople, the aldermen exercised supervisory powers over all the London guilds, and saw to the enforcement of the manifold regulations concerning public health, weights and measures, the organization of the City’s markets and the general welfare of the community. To them was also entrusted the care of orphans, whose interests they watched over solicitously.

Mayoral elections were held every year on 13 Oct. at the Guildhall. The procedure was rather less democratic than might at first appear, since although every citizen was theoretically entitled to cast his vote, practical as well as political considerations had led the court of aldermen to limit the franchise to those who received a personal summons. Besides performing the usual administrative and ceremonial duties, the mayor had to act for the Crown as both a j.p. and escheator of London and Middlesex; and for this reason only those aldermen who had served a term as sheriff were considered eligible for office. The commoners present at the Guildhall put forward the names of two candidates, one of whom was chosen by the court of aldermen. Whatever went on behind closed doors, open contests were most unusual, no doubt because the authorities did their best to discourage factionalism. In 1389, during the aftermath of all the troubles caused by John of Northampton, Adam Bamme’s supporters (most of whom had previously agitated for reform) failed to get him elected, although he was approved in the following year, by which time he had modified his political position to promote reconciliation. The mayor’s influence and prestige went far beyond the walls of London, for as the City’s most senior official and spokesman he was accorded an honoured place in society at large. Even if, as on the occasion of Henry V’s appeal for contributions towards his French campaign of 1415, the Crown was most respectful when it hoped for ‘great kyndenes and subsidie’, the mayors of London could none the less reflect with pride upon the increasing dignity attached to their office during the early years of the 15th century.16

On the other hand, election had many drawbacks, not least being the heavy demands made upon the successful candidate’s purse and time, factors which, of necessity, made the mayoralty the preserve of the very wealthiest citizens alone. The financial burdens were considered so great that in 1424 an ordinance was introduced to excuse anyone from serving three times as mayor or from being elected twice within less than seven years. In his capacity as a j.p. the mayor presided over his own court as well as the court of aldermen: the former body, like the latter, discharged many functions, moving from legal to administrative business on a largely pragmatic basis. The mayor also exercised a final authority over the sheriffs’ court, which dealt with cases concerning ‘foreigners’ (persons who were not freemen of London as opposed to aliens, who came from abroad), and a variety of civil suits. Although they were far older institutions, both the court of husting and the sheriffs’ court had by our period lost much of their earlier popularity to that of the mayor and aldermen.17 The two sheriffs were nevertheless kept extremely busy with the general task of peace-keeping in the City—a task often made difficult because they were answerable to the Crown as well as to the civic authorities, who did not always see eye to eye. London, as a shire-incorporate, enjoyed the right to choose its own sheriffs, one being appointed by the mayor and the other by the commonalty. Between them the two men were accountable at the Exchequer for the City’s fee farm of £300, they also assumed responsibility for the custody of prisoners, and as officers of the peace they were assisted by a large permanent staff of clerks and serjeants.

London first returned MPs to Parliament in 1283 and did so regularly from then onwards, although it was not until 1355 that the unique practice of electing two aldermen and two commoners was firmly established.18 Until then the writ usually specified that two or three ‘discreet merchants’ should attend Parliament; sometimes as many as six names were put forward, however, evidently because the candidates deputized for each other when pressing business commitments prevented regular attendance in the Commons.19Such practices ceased well before our period, when to be chosen as a representative for London was invariably regarded more as a privilege than an unwelcome obligation. Thanks to the survival of the City’s Letter Books, which provide the names of the Members in 11 of the Parliaments for which returns have been lost, we know who sat in 30 of the 32 Parliaments held between 1386 and 1421. The City was represented by at least 71 men over these years, but since the elections held there in 1393 and 1401 remain undocumented this figure was probably rather higher. Of the 71, no less than 40 appear to have sat only once, eight sat twice and a further eight three times. Four of their colleagues attended four Parliaments and three served in five. Eight Members had rather more experience of the Lower House. Drew Barantyn, Thomas Fauconer, John Mitchell, John Organ, John Welles III and Nicholas Wotton each sat six times, Adam Carlisle seven and John Hadley 11 times, spread over a grand total of 43 years. Hadley, Organ and William More I were, moreover, appointed to the committee of merchants to whom the Commons referred the question of a royal loan in May 1382, so it looks very much as if one or two of them were already present at Westminster.

A study of the London returns during the late 14th and early 15th centuries shows a growing desire on the part of the electorate to strike a balance between the experienced parliamentarian and the novice. Many citizens welcomed the opportunity to consolidate or establish their reputations by representing the City, but only once, in 1416 (Oct.), did four apparent newcomers sit together. One experienced Member and three novices were returned to ten Parliaments during the period under review; two experienced Members and two novices sat in a further ten, and one novice alone in five. All of the candidates who represented London in 1413 (Feb.), had served before, and it is worth noting that each of them was re-elected to Henry V’s first Parliament in the following May, probably because the business of the House was interrupted by Henry IV’s death. So many MPs had served in the Commons, and so many were anxious and qualified to gain such experience that no other instances of complete representative continuity are known to have occurred in our period. John Hadley was re-elected in 1386, William More I in 1390 (Nov.), John Prophet II in 1404 (Jan.) and William Waldern in 1415, but only in the exceptional circumstances of 1413 did more than one single individual sit in consecutive Parliaments. Two or three prominent citizens were returned rather more frequently during the 1380s and early 1390s, the tendency towards a preponderance of new Members becoming slightly more apparent from then onwards. Despite the status which the majority of the MPs considered here enjoyed as landowners in several English counties, only three were also returned as shire knights. Walter Gawtron sat twice for Middlesex, while Robert Whittingham and William Standon were returned once each for, respectively, Hertfordshire and Cambridgeshire. But whereas Gawtron and Standon both continued to take an active part in civic life, Whittingham had abandoned his mercantile interests and become a crown servant when the county electors chose him in 1432. No Londoners sat for any other borough during our period.

Since London was a shire-incorporate, the parliamentary writ of summons was sent directly to the two sheriffs. The latter were then supposed to hold the election in the court of husting, where all the freemen of London, as suitors, theoretically constituted the electing body. From the late 13th century onwards, however, the choice of Members was in fact made by a smaller, select group comprising the mayor, all or most of the aldermen and four or six ‘better and more discreet’ representatives from each of the city wards, who belonged first to the common assembly of London and subsequently to the newly organized common council. The statute of 1406, aimed as it was to prevent the monopolization of the franchise by individuals or narrow factions, set out to limit the power of the senior members of the civic hierarchy by reviving elections in the full county court. Yet although the returns often state that candidates were chosen in pleno hustengo, this was little more than a device intended to comply with the letter rather than the spirit of the statute. The names of the MPs may, perhaps, have been submitted to the husting for formal ratification, but in practice the mayor, aldermen and common councillors continued to direct matters exactly as before.20 It should not, however, be thought that the franchise was completely dominated by a narrow mercantile oligarchy. In point of fact, elections held in the court of common council were comparatively open, and there is nothing to suggest that any freeman who wished to participate was prevented from doing so. An analysis of witnesses to the ten returns which survive between 1407 and 1421 reveals that the commoners almost always out-numbered the aldermen and that members of the craft and artisan guilds were beginning to play a significant part in the choice of MPs. Nor are all voters known to have been members of the common council or holders of civic office. Election procedure was essentially pragmatic, for on certain occasions, as in 1421, all four MPs were chosen in the court of aldermen, while on others the court of common council elected its own two representatives separately (this being the case in 1419). No instance of aldermen as well as commoners being returned by the latter body is on record during our period, although this practice became quite usual in the 1440s and 1450s. In the interest of speed and efficiency, elections generally took place on Mondays at the Guildhall, because the court of husting was then in session and the sheriffs could be notified of the result at once.21

The rulers of London set great store upon their choice of representatives, and, implicitly, upon the status and respect which they were accorded in the Commons. It was unthinkable that the City’s four MPs should be overshadowed by any other burgesses, particularly in the matter of dress, and to this end a clothing allowance was supplied at almost every Parliament. Many Members must have outshone the nobility, for in 1425 and again in 1429 the court of aldermen passed sumptuary regulations designed to curb their representatives’ extravagance. Ordinary expenses were only paid when Parliament met other than at Westminster, and because of this the authorities could afford to be extremely liberal. Civic pride also played its part in their decision to vote 20s. per day to the Members who sat in 1290, since no other city in England could afford to spend even half this sum on expenses.22 The claims submitted to the chamberlain of London seem to have grown larger as the 14th century progressed, and there were times when he had either to borrow money or levy extraordinary taxes to meet them. The four MPs who sat in the Cambridge Parliament of 1388 spent a total of £112 7s., partly on repairs and alterations to their hostel, which was evidently unsuitable for such eminent lodgers. They made gifts to the minstrels of the King and other lords, and paid over £22 for new vestments. Their entourage included a steward, butler, cook and kitchen boys, as well as grooms to look after the horses. These expenses may have been somewhat heavier than usual, since it was in the Cambridge Parliament that the royal council was authorized to make a general inquiry into the customs and possessions of all English guilds. The Londoners, considering such an inquiry to be against their vested interests, no doubt attempted to win as many influential friends as possible. Indeed, on this occasion, reserves from the Guildhall were set aside to pay expenses, as the chamberlain had not enough cash in hand. The decision to hold Parliament away from Westminster, its customary venue, was on this, as on other previous occasions, largely dictated by the government’s fear of the London mob. Contemporaries certainly believed that Parliament had been summoned to meet at Gloucester in 1378 and Northampton in November 1380 because John of Gaunt in particular was so deeply unpopular in London.23

The trades and crafts of London were organized into guilds, whose functions were as much political and social as they were economic. Like the government of the City itself, they were dominated by an elite of richer, more successful merchants or artisans, and tended in consequence to be run on authoritian, often repressive lines. Except in a few cases entry to a guild was gained only after a long period of apprenticeship, the terms and conditions of which were laid down by the authorities. The wardens and masters of the city companies were vested with considerable powers, acting as agents of the mayor for the enforcement of disciplinary and economic regulations. The rulers of the more important mercantile companies, such as the Drapers, Mercers, Grocers and Goldsmiths, enjoyed great influence in the community as a whole, since they represented a major force in civic politics. The resentment felt by the craft and artisan guilds on this score, coupled with a widespread dislike of trade monopolies (most notably that exercised by the Fishmongers) among the populace as a whole had provided John of Northampton with a platform during the early 1380s, but although certain rivalries and changes in the fortunes of particular companies are clearly discernible over the next 40 years, ours was not a period of intense antagonism or social conflict. With the exception of Andrew Newport, a squire of the body to Richard II, who sat as a royal placeman in the Parliament of September 1397, all the Members returned for London between 1386 and 1421 were either merchants or artisans belonging to one (or in a few cases, two) of the city guilds. The Grocers provided London with no less than 18 MPs, two members of their company being returned together to nine Parliaments, and one sitting alone in a further 16. Almost as influential in terms of parliamentary representation were the Mercers, 16 of whom served during our period, although rather less often than the Grocers. Two mercers are known to have been present in four Parliaments and one in 15. The rise to prominence of the Drapers’ Company is evident from the corresponding frequency with which its members came to be returned. Only one draper (John Walcote) sat before 1402, his election clearly owing more to his personal wealth and position than his association with one of the then less affluent guilds. Yet between 1402 and 1421 a further 11 drapers entered the Commons: two sat together in the Parliaments of 1414 (Nov.) and 1421 (Dec.), and one alone was returned on 13 other occasions over the two decades. The Fishmongers, on the other hand, lost much of the power which had made them so unpopular during the 1380s. Ten members of their company represented the City in as many Parliaments, but it is worth noting that John Mitchell also described himself as a grocer, and that, until the ordinance of 1415 prevented Londoners from wearing more than one company livery, both Nicholas James and Richard Marlow were ironmongers as well. A similar decline is apparent in the case of the Vintners, who had no representative at all in the Commons during the early 15th century. Only five members of the Company sat between 1388 and 1397, although two were present at Cambridge in September 1388. Whereas no more than four goldsmiths are in evidence during the period under review, they served in at least ten Parliaments at fairly regular intervals. The same number of ironmongers were returned, two sitting in March 1416 and one in six Parliaments from 1399 onwards.

Representatives of the humbler craft and artisan guilds were not often chosen by the electors of London, partly because the far richer mercantile companies—particularly the Mercers and Drapers—dominated the court of aldermen and the common council, but also on account of the comparatively lowly status accorded to those who earned money by working with their hands. Thus, even though the Tailors’ Company was wealthier and longer established than that of the Drapers (having had a master since 1390, a hall since 1392 and a royal charter of incorporation awarded in 1408), none of its members became either aldermen or MPs during our period.24 Few artisans rose to occupy high civic office, and three of the four who sat in Parliament between 1386 and 1422 had exceptional backgrounds. Of the four, both Robert Ashcombe, the embroiderer, and Henry Barton, the skinner, held posts at Court, Barton being a man of great wealth and influence. Thomas Girdler, who may perhaps have been a mercer rather than a girdler, was the son of a former sheriff and held a fairly eminent position in the civic hierarchy. Even the saddler, Simon Sewall, was among the leading residents of his ward, which he represented on the common council. It was particularly important for a guild to secure the return of one of its members to the House of Commons when company business came before Parliament. Thus, in 1386, John Organ, one of the most celebrated ‘folk of the Mercerye of London’, was sitting when the Mercers presented their petition against Sir Nicholas Brembre†. Alarmed at the threat posed to its trade monopoly by the cutlers, the Goldsmiths’ Company addressed an appeal to the January Parliament of 1404, requesting that its powers of search and governance should be confirmed and the activities of its rivals stopped. Drew Barantyn, the leading goldsmith of his day, must have played a prominent part in the drawing up and presentation of this petition, since he was then serving as one of London’s four MPs and could supervise matters in person.25

Between them the 71 MPs under consideration possessed a remarkable degree of administrative skill and financial expertise acquired through their involvement in civic government and trade. The partial—and in certain cases almost complete—loss of the records of certain livery companies for our period now makes it impossible to tell how many men served as masters or wardens of their guilds, but on the basis of the surviving evidence, which is fullest for the Grocers, Mercers and Goldsmiths, we may presume that the great majority did so at some time in their lives. Of the 40 who are known to have held office, nine were chosen at least once, 16 twice, six three times, and five four times. Thomas Fauconer served five times as warden of the Mercers’ Company, while the goldsmiths, Thomas Exton and Solomon Oxney, were both wardens of their guild six times. John Welles III appears to have been the most experienced, with no less than seven terms as warden of the Grocers’ Company to his credit. It is interesting to note that most of them had been elected to office at least once before they first sat in Parliament. Indeed, 30 in all entered the Commons as wardens or former wardens of their guilds, while a further seven assumed such posts during the course of their parliamentary careers. No more than three became wardens after the date of their last return.

Thanks to the wealth of information available in the city archives we can speak with far more certainty about the part played by each MP in the government of London. The office of mayor was held by 27 different individuals, 13 serving for one term, a further 13 for two, and one, the celebrated Richard Whittington, for three. Predictably, in view of his importance in national as well as civic affairs, the mayor of London was almost always an established figure of mature years. Nine of our Members assumed office after their time in the Commons was over, and 12 were elected in between periods of parliamentary service; only six had already been mayor when they were first chosen to represent the City. None held office at the time of their election. In contrast, about a third (17) of the 47 MPs to be made sheriffs of London had occupied the post before being returned, and a further 14 went on to do so during the course of their careers in the Lower House. This particular shrievalty was regarded as a stepping-stone to higher things, so nobody was expected to serve more than one term. As we have seen, by the mid 14th century the City sent two aldermen and two commoners to every Parliament, an arrangement which, on numerical grounds alone, gave each alderman a far greater chance of being elected and thus worked to the advantage of the established order. Since the more distinguished citizens usually held aldermanic rank and tended, with the notable exception of Richard Whittington, to be returned to two or three Parliaments at least, this select group also boasted a striking amount of corporate parliamentary experience. Of the 71 Members discussed here, 25 were aldermen when first returned and 12 more eventually entered Parliament as such. This leaves us with 34 men who sat far less often and only as commoners, although 11 of them were made aldermen in later life. Yet it should not be assumed that those who did not rise to the top of the civic hierarchy were denied the opportunity to exercise their administrative talents. No less than 52 of our MPs were chosen to audit the accounts of the city chamberlain and the wardens of London Bridge, despite the fact that only three appear to have served as wardens themselves, and one alone (John Prophet) ever became chamberlain. The composition of the common council is harder to establish, but it seems more than likely that membership of this body, at some time or another, was a prerequisite of election to Parliament.

Many Londoners had experience of working on both royal and civic commissions. The latter, which were customarily set up by the common council or court of aldermen to investigate and advise on financial, administrative and judicial matters, involved at least 33 and probably far more of our MPs, of whom at least a third sat on more than six commissions at various times. Whittington’s total of 25 is particularly outstanding: indeed, the part he played in the government of London seems to have been greater than that of any of his contemporaries. The same number of individuals (that is 33) were made tax collectors (either for the Crown or the commonalty) and assayers of goods offered for sale in the City, usually while they were still comparatively young and lacking in other administrative experience. Given, however, that Londoners did not as a rule gain full admittance to their guilds or companies before reaching the late 20s, at least, their careers took far longer to get established. Those serving on royal commissions tended, on the other hand, to be among the richer, more powerful and therefore usually older citizens. Merchants who possessed country estates sometimes acted as local commissioners of inquiry or of sewers, but it was their specialist knowledge which made them particularly useful to the Crown. Most of the 23 MPs who sat on royal commissions during our period were either called upon to investigate commercial disputes and cases referred from the court of admiralty or else to administer justice in the City. Several of them showed such ability that they went on to assume a more central role in national affairs. Richard Whittington, William Brampton I and John Shadworth were together admitted to the royal council during the first year of Henry IV’s reign—a gesture which shows clearly enough how much importance Henry attached to the continued support of the City. Brampton later became deputy admiral of the western fleet, but like John Organ, a deputy keeper of the seas for Richard II, and Richard Marlow, who was treasurer of the wars and then treasurer of Calais for Henry IV, he did not actually attend Parliament as an office-holder. William More I was returned in 1379 while serving as deputy butler of Sandwich, however, and John Hadley, intermittently a treasurer of the wars for both Richard II and Henry IV, sat as such in no less than four Parliaments. Although he became an alderman shortly before representing London in September 1397, Andrew Newport was essentially a crown servant, then acting as warden of the Mint and keeper of gold and silver stamps at the Tower. Preferment came to Robert Whittingham long after his career as a London draper was over: in later life he occupied a number of important administrative posts, including the receiver-generalship of both the duchy of Cornwall and the estates of John, duke of Bedford, and the treasurership of Calais. John Welles III was made keeper and escheator of Norwich, and William Sevenoak surveyor of the King’s works at Isleworth, again after they had both ceased to sit in Parliament. Andrew Newport’s appointment as sheriff of Hertfordshire and Cambridgeshire came to him through his position at Court, but it was not uncommon for Londoners to hold offices outside the City, especially when these brought with them commercial advantages. The drapers, William Norton II and John Gedney, were alnagers of Middlesex, and their colleague, John Brockley, alnager of Rutland and Northamptonshire. William Brampton I, a fishmonger, was made bailiff of Southwark (through which a large part of London’s fish supplies had to pass). Robert Whittingham, the only Londoner to make a complete transition from merchant to country gentleman and royal servant during our period, became so established among the Hertfordshire gentry that he was appointed sheriff as well as a j.p. there.

Many avenues were open to the ambitious Londoner with mercantile experience or a talent for administration. At least 12 MPs, if not more, were involved in the running of the Westminster Staple, an organization concerned largely with the mechanics of taking and enforcing recognizances for debt. Seven of them became mayor, four served as constables and one, Nicholas Wotton, occupied both offices during the course of a long and distinguished career. Service on embassies abroad, which was performed by ten of our Members, was generally confined to the negotiation of commercial treaties with foreign powers, since it was here that the merchant with overseas interests could best use his experience and influence, particularly when he had business connexions of his own to exploit. Thus, for example, John Clenhand, William Askham, William Brampton I, Thomas Newton and John Reynwell, all of whom were among the city’s leading exporters of wool, were dispatched at various times on embassies to the Netherlands, where they were already well known. With the exception of Robert Whittingham, a crown servant by the time of his first diplomatic appointment, each of these men represented London at least once after taking part in such missions, so they were clearly well qualified to speak on foreign policy, if required to do so.

Although many Londoners came to occupy the higher civic offices after gaining some parliamentary experience, a working knowledge of the government of the City, acquired either in minor posts or through membership of conciliar committees, seems generally to have been expected of those who sought election to the Commons. Only 12 London MPs were apparently returned without any such qualifications, although we can safely assume that they must, at the very least, have already been made common councillors. Moreover, since most of them belonged to guilds whose records have been either partially or completely lost, there is a strong possibility that some had acted as the masters or wardens of their companies. Only one of their number, the fishmonger, Hugh Ryebread, did not subsequently hold office in the City or receive any post or commission from the Crown. In marked contrast to the generally high level of familiarity with local administration, far less than half (27) of our men had ever been royal commissioners, ambassadors or government employees before entering the Lower House, although they soon made up for this lack of experience as their careers progressed.

The mercantile interests of the Londoners here under review were extremely diverse, for even members of the craft guilds found it expedient to trade in a variety of different commodities. Some companies—most notably the Mercers—were more successful than others in their attempts to establish a commercial monopoly, but none was entirely able to prevent other merchants from competing in the same field. Because the London customs accounts for our period are so fragmentary, we cannot now determine the extent or diversity of each individual’s investment in trade, yet even with the limited evidence at our disposal, it is clear that very few, if any, dealt only in one type of merchandise. A bare minimum of 44 MPs did regular business overseas, the mercers and drapers among them in particular having connexions in Italy. Involvement in the wool trade, which provided England with her ‘cheeff richesse’ at this time, was widespread: at least 30 of our men had some interest in the export of wool, and most of them relied heavily upon it as a major source of income. Some, like Richard Whittington and Drew Barantyn, were initially obliged to invest in wool as a means of recovering money advanced by them to the Crown and repaid in the form of exemption from customs dues. Others, of whom John Clenhand and John Walcote are the most striking examples, were principally ‘woolmongers’ although they belonged to the Drapers’ Company. A period as collector of customs in London or some other southern port probably encouraged certain merchants to exploit foreign markets. It seems that 11 or even more of the 18 MPs who became customs officers engaged in the export of wool, having in some instances been appointed so that they could more easily collect what was owing to them at the Exchequer. Loss of evidence prevents us from discovering the names of all the mayors of the Calais Staple in office during the late 14th and early 15th centuries: at least five of them were London MPs returned during our period, of whom four are known to have been prominent wool merchants. The importance of the Staple, not merely as a legislative and administrative body concerned with the regulation of the wool trade, but also as an organ of public finance, meant that only the most influential and experienced men held this office, either towards the end of their parliamentary careers or after they had ceased to sit in the Commons. Richard Whittington, who was comparatively old at the time of his one return to Parliament in October 1416, was exceptional in entering the Commons with his term as mayor behind him, although William Brampton I had served as governor of the short-lived Staple at Middleburg before being returned. There can be little doubt that legislation dealing with the wool trade in general and the organization of the Calais Staple in particular was of immediate concern to almost all London’s MPs, a large number of whom were themselves members of the fellowship of the Staple, and thus personally committed to defending its privileges. Their interest found expression in several of the petitions addressed by the staplers to Parliament during the period under review.

Many London MPs contributed towards the corporate loans advanced to the Crown by the Calais Staple and the City, although we cannot now determine the size of their several contributions. The royal government also borrowed heavily from individuals, despite the fact that the days of the great speculative financiers like the draper, Sir John Poultney, and the vintners, Henry Picard and Richard Lyons†, who had flourished during the earlier part of the 14th century, were long since over. Changes in the organization of the English wool market, of which the development of the Calais Staple proved the most far-reaching, were in part responsible for the disappearance of these entrepreneurs, but fear of bankruptcy and the dire political consequences of becoming too closely involved in government finance acted as disincentives upon others with money to lend. The merchants who, in 1382, declined to raise a royal loan of £60,000 on the ground that they might later share the fate of Edward III’s leading creditors, expressed a view commonly held in mercantile circles.26 Yet although our MPs were not on the whole prepared to advance money on the same scale as their predecessors, a number did play a significant part in the financial affairs of the Crown. Their loans took the form of either cash or bonds to be repaid over a specific period or else of goods supplied to the royal household on long-term credit.

The Crown borrowed money from at least 36 of the men who represented London during our period, and their pattern of lending clearly reflects the changing relationship between the Court and the City in the late 14th and early 15th centuries. Three of our MPs made their most substantial loans during Edward III’s last years, and three during the earlier part of Richard II’s reign. The strained atmosphere of suspicion and distrust which characterized Richard’s dealings with London from 1392 onwards made the citizens unwilling to supply him with personal loans, especially as they were also obliged to contribute to the heavy impositions which he placed upon them during this period. A small group, including Richard Whittington, the most prominent of Richard’s creditors, continued to lend money, but the majority tightened their purse-strings. Their comparative open handedness to Henry IV and his successors was largely a matter of self-interest: having finally given their support to the house of Lancaster the rulers of London were committed to keeping it upon the throne. As their corporate and individual loans grew in size, so too did their reluctance to risk the possibility of financial loss inherent in a change of dynasty. These loans have been described as ‘the oil with which the City lubricated the lumbering machine of royal favour and patronage’, and it is quite evident that the people of London, chastened by their experiences in the 1390s, were afraid of precipitating any further displays of royal displeasure. Richard II’s seizure of the City’s liberties in 1392 was largely prompted by his exasperation at the repeated refusals which had met his earlier appeals for money. Summoning the aldermen and other leading oligarchs before him at Nottingham by a writ ‘so fearsome and utterly hair-raising as to cause the ears of whoever heard it to tingle’, the King was actually prepared to suspend the normal government of London; and all in all, it may have cost the citizens £30,000 in exactions, gifts and entertainments to buy their way back into his good graces. Fear and prudence made them more circumspect in their dealings with Richard’s immediate successors, who benefited from the harsh lesson which he had taught, while at the same time learning from his mistakes.27

Having most to lose from any challenge to the City’s privileges, the sheriffs and aldermen were particularly receptive to demands for financial assistance, not only in a private capacity but also when it came to making up the sums promised by the common council on behalf of the citizenry as a whole. Of the 36 royal creditors considered here, 13 made their largest single loans to Henry IV, 12 to Henry V and 11 to Henry VI. Even Whittington was prepared to advance money on a rather more impressive scale to the Lancastrians than he had done in Richard II’s reign. Although considerably less than the massive amounts raised by Edward III from certain Londoners, the sums involved were by no means negligible. An analysis of royal borrowing after 1400 shows that 21 London MPs lent a minimum of £50 to the Crown on one occasion at least, and that six of their number were each owed more than £500 for loans made either in cash or as extended credit for goods. Thus, in 1402, the mercer, John Woodcock, was awaiting payment for merchandise worth £2,330 which he had supplied to the royal wardrobe while continuing to lend separate sums of up to 500 marks at the Exchequer. The same is true of Richard Whittington (whose largest cash loan of £2,833 was made in 1408) and the goldsmith, Drew Barantyn, who advanced £1,000 to Henry IV in 1410. Merchants of this stature were usually given priority over less influential royal creditors at the Exchequer, being promised repayment from sources of revenue to which they had ready access. The two most common types of assignment took the form either of a licence to export wool free of customs duties to the value of the original loan, or of a charge made directly upon the customs paid by others. Men like Henry Barton and William More I were ideally placed as customs officers to recover their debts at once, although most city merchants could be reasonably sure of obtaining preference, so close were the ties which existed between them and the port officials.

Questions of government finance—particularly regarding the award and allocation of subsidies by Parliament—were thus of vital importance to most London MPs, who had personal as well as general interests to protect. We cannot now determine whether or not their loans were in any way usurious: it is, however, clear that the City did not charge a rate of interest when making corporate loans to the Crown; and, as we have seen, other motives besides financial gain led the individual merchant to become a royal creditor. Whatever his faults, Richard II was a notable and discerning patron of the arts, whose lavish expenditure on his court and household lined the pockets of a small but powerful group of Londoners. The mercers, Richard Whittington and John Woodcock, both prospered through Richard’s patronage, as did the embroiderer, Robert Ashcombe. Drew Barantyn, Henry Barton, John Whatley and other suppliers of the Lancastrian household likewise found that, despite the length of time that they might have to wait for repayment, their connexion with the Court brought many real advantages. In all, at least 21 of our MPs provided the royal establishment with merchandise at various times. Predictably, perhaps, many of those with whom Henry IV’s agents did business had supplied his household in the previous reign, or (as was the case with both Barantyn and Barton) had been patronized by his father, John of Gaunt. Yet only seven of our men, including Andrew Newport who was primarily a courtier, actually held offices in the royal household. William Askham, William Burton I, John Mitchell and William Standon all served as buyers or purveyors; Robert Ashcombe was embroiderer to Richard II, and Henry Barton King’s skinner from 1405 to 1433.

Given that the aldermen and wealthier citizens of London were anxious to stand well with the Crown, and, in most cases, had some connexion with it either as creditors, suppliers of the Court or office-holders, attempts to secure the return of royal ‘placemen’ to Parliament were as rare as they were unnecessary. There were probably two occasions, however, on which the electors of London either had candidates forced upon them, or, as seems more likely, found it expedient to make a particular show of loyalty by choosing men favoured by the King. The loss of the City’s return to the Parliament of 1393 is indeed unfortunate, since the rulers of London were then still trying to placate Richard II after the stormy events of the previous year, and may well have used the elections as a means to this end. The return of Andrew Newport and Robert Ashcombe in September 1397 points clearly enough to a case of electoral management. Newport, a favourite of Richard II, sat as a newly made alderman, although he did not belong to any guild and was not a Londoner by birth. One of the few artisans to enter Parliament during our period, Ashcombe owed his election to his position as King’s embroider, since the City had prudently decided to make plain its support for Richard II in the last stages of his vendetta against those who had previously sought to curtail his political freedom.

It is possible to build up a detailed picture of property ownership in London from the deeds entered on the husting rolls, although the increasing popularity of the enfeoffment-to-uses (which could be employed three or even four times during the course of one transaction) often prevents us from establishing precisely to whom a particular estate belonged. All the MPs considered here occupied houses and shops in the City; and the majority clearly sought to invest their surplus capital in additional tenements which could be rented out to others. Even allowing for their activities as trustees, at least 46 of our men acquired holdings in three or more London parishes, almost half of them being rentiers on a fairly impressive scale with interests in over six parishes, often in different parts of the City. Adam Bamme and John Walcote were probably the most notable landlords, the latter enjoying an income of at least £110 a year from his wife’s London estates alone. The survival of tax returns (particularly those of 1412 and 1436) and some inquisitions post mortem enables us to estimate the minimum annual income from land in the City of well over half (44) of our MPs, although in some cases the tax assessments are both too early and too unreliable to give us much idea of an individual’s wealth at the time he was first elected. Bearing in mind, therefore, that at least 18 men bought most of their property after the returns of 1412 were compiled, it appears that only two were taxed at £5 a year, while ten netted incomes of between £5 and £9, and 15 incomes of between £10 and £40. A further six MPs fell into the higher £40-80 bracket, and it looks as if the above-mentioned Adam Bamme could probably count on revenues of over £150 a year in all. John Walcote may have been almost as rich, but his finances remain almost undocumented.

Rather less is known about the country estates which the great majority of London Members acquired, partly from a desire to establish themselves as the social equals of the gentry, but also in the hope of making a sound and remunerative investment of their commercial profits and providing for their wives and children. Many Londoners moreover derived great enjoyment from rural pursuits, and willingly abandoned their civic duties for comparatively long periods. This was a cause of some concern to Henry V, whose fear for the defences of London led him to order a number of aldermen back to their town houses before he set out on the Agincourt campaign.28 Of the 57 MPs who owned land outside London, the majority confined their interests to the neighbouring counties of Essex (the most popular), Middlesex, Kent and Surrey. Cambridgeshire, Hertfordshire and Buckinghamshire also attracted the merchant with money to invest, but those who made purchases further afield usually did so in order to consolidate an inheritance or the dower properties of their wives. Only a few Londoners seem to have wished to become landowners on a grand scale with estates in several counties: indeed, most elected to build up one or two compact holdings within 30 or 40 miles of the City. The goldsmith, Drew Barantyn, who came from an affluent Oxfordshire family, is exceptional in having land in at least eight English counties from Buckinghamshire to Suffolk. At over £100 a year, his revenues from the country were considerable but not outstanding. Nicholas Wotton, the draper, for example, owned properties worth more than £147 a year, and there may well have been others with even larger incomes. Unfortunately, we do not have enough evidence for detailed comparisons.

The striking absence in London of the great merchant dynasties to be found in other late medieval European cities has been noted by writers from Caxton onwards, and reveals a far freer pattern of social and geographical mobility than existed on the continent. Not only was it easier for the sons and grandsons of merchants to enter the ranks of the country gentry: the younger sons of gentlemen and yeomen were also quickly and successfully absorbed into the merchant class, often rising to become aldermen or even mayors within the space of a few years. Thanks to the survival of wills made by almost all of our MPs, we can be reasonably certain about the birthplace, if not the family background, of at least 64 of them. Only slightly more than half appear to have been Londoners by birth: at least 14 were definitely brought up in the City and a further 20 probably lived in London or the suburbs from childhood. Of the remainder, 14 are known to have come from outside London and there is strong circumstantial evidence to suggest that 16 others were also born in the country. Neither citizenship by birth nor the membership of an established merchant family were necessary qualifications for success in medieval London, although, as Sylvia Thrupp has shown, a strong element of social cohesion was provided by the marriage and remarriage of merchants’ widows and daughters within their own class.29

The London citizen customarily left one third of his moveable property to his wife and one third to his children, with the result that widows with young children were in particular demand. While insisting upon strict accountability for the capital sum involved, the civic authorities allowed the guardian of a child’s inheritance to keep whatever profits he might make by investing the money on his own behalf. Thus, on his marriage to Joan, the daughter and sole heir of John Walcote, Walter Gawtron not only obtained control of her rich inheritance and the dower properties settled upon her by her first husband, but also received custody of her four children and their patrimony. Not enough evidence has survived about the background of Members’ wives for us to establish exactly how many of them brought their husbands property or commercial connexions in the City, but this was probably quite common. Of the 64 men who are definitely known to have married, at least 20 had two wives, and seven, if not more, married three times. Only 33 of these marriages can be analysed in more detail, but it appears that no less than 20 of them were to widows, of whom all but two had previously been the wife of a London merchant. Robert Chichele, William Norton II and Adam Bamme were each twice married to the relicts of Londoners and, indeed, it was through his marriage to the thrice-widowed Margaret Stodeye that Bamme established himself so successfully in the City. Nine MPs, at the very least, married the widows of members of their own guilds, while four others had wives whose former husbands had belonged to trades or crafts similar to their own. A further seven married women who, although not widowed, were the daughters of influential city merchants. It is interesting to note that for their second or third wives—whom they usually married quite late in life—the more affluent MPs often chose the daughters of gentlemen or landowners. William Cromer, for example, married the daughter of Sir Thomas Squiry after the death of his first wife, since by this date commercial success made it possible for him to concentrate on his social ambitious. The mercer, William Parker I, likewise took as his second wife Joan, the daughter of John Norbury*, who subsequently became treasurer of England. In this case, however, he cannot have been unaware of the material advantages which such a connexion could offer.

Author: C.R.

Notes

- 1. In September 1390, John Loneye, alderman of Cripplegate Ward, was returned to Parliament, but another election was held on 13 Oct. and William More I was chosen in his place (Cal. Letter Bk. London, H, 355, 359).

- 2. Ibid. 404.

- 3. Ibid. I, 21.

- 4. Ibid. 36.

- 5. Ibid. 33.

- 6. Ibid. 81.

- 7. Ibid. 95.

- 8. Ibid. 109.

- 9. Ibid. 121.

- 10. Ibid. 145.

- 11. Ibid. 158.

- 12. See. S.L. Thrupp, Merchant Class Med. London, chap. 1, passim, for a description of city life at this time. A detailed account of the machinery of government in 15th-century London is to be found in C.M. Barron, ‘Govt. of London’ (London Univ. Ph.D. thesis, 1970), chaps. 2 and 3.

- 13. Mems. London ed. Riley, 601-3, 635-7.

- 14. Beaven, Aldermen, ii. pp. xiv-xv, xix-xx.

- 15. Mems. London, 491, 502-3.

- 16. Thrupp, 259-60.

- 17. See the introduction to Cal. P. and M. London, 1323-64, pp. viii et seq. and 1381-1412, pp. xii et seq. for a discussion of the work of these four courts.

- 18. Londoners were, however, present at the assembly convened under the influence of Simon de Montfort in 1265, and probably again in 1275 (M. McKisack, Parl. Repn. Eng. Bors. 1-3).

- 19. Beaven, i. 261 et seq .

- 20. McKisack, 14-16, 30-32, 48-51.

- 21. Barron, 323-32, 603.

- 22. McKisack, 82-85.

- 23. Mems. London, 511-12; Eng. Gilds (EETS, xl), 127-30; R. Butt, Hist. Parl. Middle Ages, 363-72.

- 24. Barron, 279-82.

- 25. RP, iii. 225, 536-7; T.F. Reddaway and L.E.M. Walker, Early Hist. Goldsmiths’ Company, 94.

- 26. E. Power, Wool Trade in Eng. Med. Hist. 114-20.

- 27. Reign Ric. II, ed. Du Boulay and Barron, 200-I; Westminster Chron. 1381-94 ed. Hector and Harvey, 497.

- 28. Thrupp, 227.

- 29. Ibid. 28-29, 105-7, 191, 232.