Go To Section

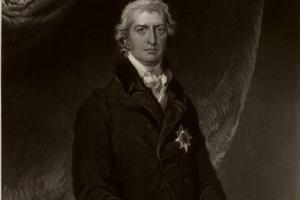

JENKINSON, Hon. Robert Banks (1770-1828), of Coombe Wood, nr. Kingston, Surr.

Available from Boydell and Brewer

Constituency

Dates

Family and Education

b. 7 June 1770, 1st s. of Charles Jenkinson†, 1st Earl of Liverpool, by 1st w. Amelia, da. of William Watts, gov. Fort William, Bengal, later of South Hill, Ascot, Berks. educ. Parsons Green, Fulham; Charterhouse 1783-7; Christ Church, Oxf. 1787. m. (1) 25 Mar. 1795, Louisa Hervey (d. 12 June 1821), da. of Frederick Augustus, 4th Earl of Bristol, and bp. of Derry, s.p.; (2) 24 Sept. 1822, Mary, da. of Rev. Charles Chester (formerly Bagot), s.p. Styled Lord Hawkesbury 1 June 1796-1803; summ. to the Lords in his fa.’s barony as Baron Hawkesbury, 15 Nov. 1803; suc. fa. as 2nd Earl of Liverpool 17 Dec. 1808; KG 9 June 1814.

Offices Held

Commr. Board of Control Apr. 1793-9; PC 13 Mar. 1799; member of Board of Trade 1799; master of Mint 1799-1801; sec. of state for Foreign affairs Feb. 1801-May 1804, for Home affairs May 1804-Jan. 1806, Mar. 1807-Oct. 1809, for War and Colonies 1809-12; first ld. of Treasury May 1812, 16 June 1812-20 Apr. 1827; commr. of treasury [I] 1814-17.

Ld. warden, Cinque Ports 1806-d.; receiver-gen. duchy of Lancaster July 1807-June 1819; master Trinity House 1816-d.

Col. Cinque Ports fencible cav. 1794, militia 1810.

Biography

Jenkinson ‘seemed born to be a statesman’: he was carefully educated for the role by his father, who aspired to it himself and who as Pitt’s president of the Board of Trade readily assumed that character, which seemed to be confirmed by his admission to the cabinet in 1791. At Oxford Jenkinson was a ‘well educated, well informed, and sensible’ member of the talented Christ Church set. One of them, Lord Boringdon, recalled in 1809 that he

was at that time, as he has appeared ever since, singularly good natured. He was much ridiculed, seldom being addressed by any other name than ‘Jenky’, excepting always indeed by Lord Molyneux, who always called him either ‘delightful’ or ‘beauteous fair one’; his manners were effeminate and cold, and were rendered still more unpleasing by an almost constant state of absence of mind either real or affected.

When his father sent him to Paris in 1789, he introduced him as ‘an excellent scholar, rather an elegant figure, of perfect morals and of a disposition that I am sure will please you’.1 An eye witness of the fall of the Bastille, he was supposed to have made his mind up there and then against Jacobinism.

Although not of age, Jenkinson was returned in two places in the election of 1790. Lord Lonsdale, whose Member his father had once been for Appleby, returned him there unsolicited, on condition only that he voted as his father did. His father had meanwhile been casting about for a seat for him and found one for Rye, where he came to terms with the Lamb family. Jenkinson thereupon gave up Appleby in December 1790, though he had to wait until the following year to take his seat. In April 1791 he was marked ‘abroad’ on a list of opponents of repeal of the Test Act in Scotland. His father put him under the same tutelage to Pitt as he had himself been to Lord Bute, and Pitt entrusted to this élève, with his airs of ‘excessive importance’, the reply to Whitbread’s critical motion on the armament against Russia for his maiden speech, 29 Feb. 1792. This exposure of Russian ambitions was an ‘amazing success’, played down by opposition to goad Pitt, but lauded by the latter, for it contained ‘more information than ever appeared in a coup d’essai’ and was delivered ‘without a falter’, for more than an hour.2 On 8 Mar. he was invited to the ministerialist meeting at Downing Street and he acted as government teller on 27 Apr. and 8 May 1792.

Jenkinson differed from his associates in opposing the abolition of the slave trade pro tem., 2 Apr. 1792, when he failed to carry two propositions to encourage the proliferation of slaves. Sir Gilbert Elliot reported:

it was a set speech, composed and delivered in mimicry rather than imitation of Pitt, but so inferior, and I think so puerile in manner in spite of all the confidence, arrogance, and conceit that could belong to a veteran, that he put me in mind of a monkey brought in to dance on the rope after a principal performer! He will do, however, in the world; for those qualities which make a man odious and unamiable in private life are very successful in public, especially when added to great application, and probably both to ambition and every other branch of the selfish and interested passions. I was on the whole, disappointed with him, but he is nevertheless an extraordinary boy. He makes more faces than his father, and is so ludicrous in action and grimace that his language has hardly fair play.

On 21 May he opposed an inquiry into the Birmingham riots and on 5 June deprecated the quotation of unauthenticated documents in debate. He then went abroad again, sending home useful reports of émigré activities from Koblenz.3

On 13 Dec. 1792 Jenkinson was deputed to stand in for the lord mayor of London if the latter arrived too late to move the address, and on 15 Dec., in Pitt’s absence, opposed Fox’s amendment for a negotiation with France, in a manner that gained Burke’s applause. He had no time for the prospect of a coalition government incorporating Fox. On 4 Jan. 1793 he defended the aliens bill and on 18 Feb., in an ‘incomparable speech’, moved the previous question against Fox’s pacific resolutions, which were easily disposed of.4 On 26 Feb. he advocated indefinite postponement of the abolition of the slave trade (modifying this on 25 Feb. 1794 to the duration of war). By 6 May 1793, when he ably opposed Grey’s motion for parliamentary reform, he was in office, as a commissioner of the Board of Control: nor, except for the interlude of 1806-7, was he ever out of it again until his last illness. He was government teller 15 times in the session of 1793. He was also a member of the committees to relieve the suffering of the French clergy and laity and to review Warren Hastings’s impeachment.

He added to his reputation in debate in the session of 1794 by defending the Dunkirk and Toulon expeditions against Maitland, 3 Feb., 10 Apr.; by defending the allied coalition against Whitbread, 6 Mar., and by answering Fox’s resolutions against the war, 30 May 1794, when he denied that the war aims had changed. It was on this occasion, two weeks after Jenkinson had been chosen a member of the secret committee on sedition, that Sheridan twitted him with being ‘so much in the secrets of ministry’, doubtless from ‘an hereditary knowledge of politics’. By then he was foremost among the young speakers, with the exception of Canning; both overloaded their speeches with quotations. But Jenkinson was not taken as seriously as he might have wished. His outburst on 10 Apr. 1794 in favour of a ‘march to Paris’ was one that he was not allowed to forget. Lord Mornington wrote:

I really cannot crouch to young Jenky whom I have laughed at ever since I have known him and my habits of considering him as a ridiculous animal are so rooted, that I am afraid I cannot easily be brought to admire him as a minister.

When he became colonel of the Cinque Ports fencible cavalry at Pitt’s instigation in April 1794, Canning, who found that Jenkinson ‘thinks and talks and cares about nothing else in the world’, reduced him to tears by putting his recruiting handbill into doggerel verse: it was some time before he was forgiven.5

In December 1794, hopelessly in love with Lady Louisa Hervey and thwarted by his father’s dislike of such a church mouse, Jenkinson threatened, with the avuncular concurrence of Pitt and Dundas, to absent himself from Parliament unless his father relented. On 20 Jan. following the scheme was thwarted by a call of the House, but he assured his father that ‘the thing must be’. The King was reported to have interceded, whereupon the obstinate parent, the ‘King’s friend’ par excellence, relented. On the eve of his marriage, 24 Mar. 1795, Jenkinson appeared in the House ‘in such spirits and such fidgets that it was quite uncomfortable to sit near him’. Meanwhile, he was able to make little contribution to debate.6

He returned to the fray on the address, 29 Oct. 1795, when Sheridan in his amendment made fun of the ‘march to Paris’, and on 10 Dec. defended the two bills against sedition, ‘the reigning crime of these days’. When not attending, he was with his regiment: he figured in debate on the subject of fencible cavalry. He now opposed the abolition of the slave trade as Jacobinical, 18 Feb., 26 Apr. 1796, voting against it on 15 Mar., and was also an advocate of the existing Game Laws, 1 Mar., 29 Apr. On 10 Mar. 1796 he sought to refute Grey’s argument against the expense of the war by reference to capital acquisitions and increased prosperity. As ‘R.B.J.’, he was the author of a pamphlet, Reflections on the present state of the resources of the country, which appeared that year.7

Jenkinson’s father was raised to the earldom of Liverpool at the dissolution of 1796 and he assumed the style of Lord Hawkesbury (‘Hawsbury’ to his satirical friends). He was again returned for Rye, despite overtures from Liverpool and Bristol.8 On 8 and 16 Dec. he made himself useful in repelling opposition motions on the imperial loan and the treatment of General Lafayette, and in March 1797 replied to Fox’s broadsides on the stoppage of cash payments by the Bank and on the state of Ireland, deprecating alarmism. On 6 Apr. he supported Ellis’s motion to encourage the regulation of the slave trade by colonial assemblies. He gave a confident and decided negative to parliamentary reform, 26 May, insisting that it would overthrow the constitution. On 1 June, being himself a subscriber to the loyalty loan, he disclaimed any benefit for himself from the bonus proposed for subscribers, which he favoured. Next session he was prominent in defence of Pitt’s assessed taxes, 14 Dec. 1797 and 3 Jan. 1798, justifying the war effort on the latter occasion; he likewise supported the sale of the land tax, 16 Apr., 30 May 1798. He helped to oppose Sheridan’s motion on Ireland, 14 June. His services were often required as teller. On 17 Dec. he defended Pitt’s income tax proposals as being ‘as near’ perfection ‘as human wisdom could devise’, and on 27 Dec. advocated them at length. He was a member of the select committee on sedition appointed on 24 Jan. and a prominent protagonist of the plan for the Irish union, 31 Jan. 1799. In March he became at once a privy councillor and member of the Board of Trade, with the office of master of the Mint, which his father assured his friends was no sinecure when his salary was raised to £3,000. For the rest of that session he was immersed in the London port improvement bill, recommending the Isle of Dogs docks scheme as chairman of the committee in June; and in bills for the regulation of the import and export of copper and corn.9

Though critical of the conduct of the Helder expedition, Hawkesbury spoke at some length on 7 Feb. 1800 against coming to terms with the French regime, and on 28 Feb. followed the cabinet line that while the restoration of the Bourbons was not a necessary aim of the war, the best security for peace would be a monarchical government in France. On 25 Apr. he reverted to the defence of the Irish union, for which he became a commissioner, as a measure of national security, without befriending Catholic relief. On 8 May he contended that the time was not ripe for peace negotiations. His chief labour that session was the carrying of the London Bread and Flour Company bill, entrusted to him by Pitt and managed, as his father proudly proclaimed, ‘almost alone’ by Hawkesbury. The joke was that ‘Jenky had taken up scarcity, from having been told to make himself scarce’. He also undertook the defence of the system of corn bounties. In November and December 1800 he made himself useful to government in defence of the Egyptian campaign and of the suspension of habeas corpus.10

Having congratulated Addington on his re-election to the Chair, 22 Jan. 1801, Hawkesbury moved the appointment of Mitford as his successor on 11 Feb., after Addington had undertaken to form an administration. He was reported to have declined the Admiralty. In fact he succeeded Lord Grenville as Foreign secretary with Pitt’s blessing and joined his father in the cabinet. Though re-elected at Rye on 25 Feb. he hesitated to take his seat owing to an uncertainty as to whether he was disqualified as third secretary of state, but this was resolved in his favour after a debate on 19 Mar. When he made his first speech in his new capacity, 27 Mar., confident that he could vindicate the country against French charges of breach of faith, he had already embarked on his chief task in office, the negotiation of peace. He was also one of the mainstays of a government weak in debating talent on other questions, such as martial law in Ireland (having been on the Irish secret committee) and the suppression of sedition generally.11

As Foreign secretary, Hawkesbury, though ‘ambitious beyond his years’, did not impress. With every predisposition to favour him, the King thought him inadequate: ‘he had no head for business, no method, no punctuality’. He was at first ‘very helpless’ and was soon adjudged ‘not by any means equal to the task imposed on him’. Dundas had thought he might make a good chancellor of the Exchequer. Nevertheless he was able to divulge the signing of ‘honourable’ peace preliminaries on 1 Oct. He could count on Pitt’s support, having consulted him ‘throughout’ and, as it turned out, on Fox’s concurrence; his chief opponents, to his dismay, were his predecessor in office Lord Grenville and his allies. His defence of the preliminaries on 3 Nov. 1801, while rendered ‘extremely ludicrous in the division of the subject into the time, the tone, and the terms, or, as was said, the triple T’s’ and reckoned disrespectful to Pitt, was described as ‘able and successful ... beyond former character’, and after his defence of the pacification of the armed neutrality of the Baltic powers on 13 Nov., the same observer, Isaac Corry, reported: ‘his character in the House rises daily and justly. His speech was better than that on the peace.’ Lord Muncaster praised ‘the most chaste speech of a man of business I almost ever heard’. Canning, unable to swallow the new administration, voted Hawkesbury ‘much the best of them’.12

In the interval before the ratification of the Treaty of Amiens, 26 Mar. 1802, Hawkesbury sparred with Grenvillite critics of the peace in debate and aided Addington in debates on Ireland and the Prince of Wales’s debts. On 29 Apr. he laid the treaty before the House and after replying to its critics delivered his vindication of it on 13 May. It was a defence of splendid isolation: his faith in the peace could not extend to a commercial treaty with France. On the address, 23 Nov. 1802, he met with more jaundiced views from Fox and Canning, and his reply, though boosted to his father as ‘admirable’, was in other quarters thought ‘very lame’. Even when on 2 Dec. he justified a precautionary military establishment against Fox, in a tone which Pitt might have inspired, Addington shrank from such boldness; and Pitt now refused to advise him. There was a rumour that, with Castlereagh now in the government, Hawkesbury might go up as Home secretary to the Lords, where reinforcement was needed; but it was agreed that his loss would be sorely felt and he remained for the present where he was.13 In justifying an isolationist foreign policy in reply to Thomas Grenville on 9 Dec. 1802, he complained of a campaign to secure the dismissal of ministers ‘without cause assigned’. He was a spokesman for government on the Middlesex petition, against Burdett, 7, 20 Dec., on the Admiralty inquiry, 13 Dec., and on 7 Feb. 1803 defended the renewed stoppage of Bank payments against its critics.

On 9 Mar. 1803, when defensive precautions against French aggression were announced, Hawkesbury defended his conduct towards France, which he was sure was irreproachable even if war ensued. Two days later, in reply to Fox, he justified the vote of supply as a prudent countermeasure. On 6 May, with war imminent, according to Grey he ‘sat shaking like a man under sentence of death’ when he put in his plea for the adjournment of the House. The need for more adjournments before the final rupture of negotiations with Buonaparte further exercised his nerves, and on 20 May he had to meet a barrage of opposition questions when he justified the rejection of the Russian offer of mediation. On 24 May he made ‘a very elaborate speech of two hours, containing little inflammable matter, and being a fair and reasonable representation of his case and justification of the war’. It incorporated what were jocularly referred to as his ‘seven good reasons for not giving up Malta’. In his ensuing call to arms, Pitt pointedly referred to Hawkesbury as ‘his noble friend’. On 27 May he moved the previous question against Fox’s pacific motion, which he alleged had no parliamentary ground or use, and asserted that the Russian offer of mediation came too late to avert war. On 1 June his father wrote approvingly: ‘You are ... the principal ornament and support of the present government, and Mr Addington is in truth little more than an instrument supported by you; if you withdraw your support and countenance he would fall at once’. The point of his letter was to argue against Hawkesbury’s going up to the House of Lords, evidently as Home secretary, to take the lead there, which was again sur le tapis, the Speaker having reported on 22 May, ‘Lord Hawkesbury is to go up to the House of Lords immediately after these questions’. Liverpool urged that as Addington could not last and Pitt’s health was poor, his son might look to the premiership: it would therefore be premature to accept the elevation, particularly as Liverpool was being asked, as a corollary, to give up the duchy of Lancaster, with its yearly increasing income, as part of the arrangement.14 A decision was suspended until the session was over.

On 3 June 1803, in what he described as his most painful speech, Hawkesbury opposed Pitt’s deliberate evasion of Patten’s censure motion and called for a vote of confidence in government. He spoke by all accounts ‘uncommonly well’ and Pitt got nowhere, but the ‘utter despondency’ of Hawkesbury’s tone and the perturbation of his manner were remarked upon. During the rest of the session he spoke in support of the unlikelihood of a French invasion of England, 30 June, and advocated the property tax, 5 July, the defence bill, 18 July, compensation to the House of Orange, 25 July, and government policy in Ireland, 28 July, 11 Aug., replying on the latter occasion to Hely Hutchinson’s motion. On 17 Aug. his father resigned the duchy and on 15 Nov., Hawkesbury was summoned to the Lords, where he was to lead for government against Lord Grenville’s opposition. At that time, according to Robert Ward*, he stood ‘the highest in the estimation of the politicians’ and the move was thought to have been prejudicial to him.15

Yet he proved irrepressible: demoted to the Home Office by Pitt in 1804, he regained the King’s good opinion, brought about the temporary reconciliation between Pitt and Addington and was invited, but declined, to take over the Admiralty in 1805 and the government on Pitt’s death in January 1806. Compensated with the wardenship of the Cinque Ports, he was prominent in opposition to the Grenville ministry and encouraged the King to resist them over Catholic relief. He returned to the Home Office in Portland’s government in 1807 and, after taking over the secretaryship for War and Colonies under Perceval in 1809, was his colleagues’ choice to succeed Perceval as premier in 1812. Defeated almost at once, he was reinstated and served as premier for 15 years. He was, in Brougham’s estimate ‘a good, plain man of business ... a man of the pen and the desk like his father before him—and who never speaks when he is not wanted’. To ‘respectable mediocrity’, he added ‘extraordinary prudence’ and ‘rare discretion’, with the result that ‘while great measures were executed, no one thought of Lord Liverpool’. This was how a country gentleman saw him:

He had a meek spirit—too meek for a premier—and Canning’s overbearing temper was too much for him: but he was a far wiser statesman than Canning, though not, like him, a splendid rhetorician. He was too much of a Tory in his principles, which had been bred in him; but he was very mild in their application. Though he had abilities and great knowledge, he had not genius; he could not originate, but he could judge with calmness and correctness on the data submitted to him, though perhaps not very quickly. I have no doubt that he meant honestly, and had the interests of his country at heart.16

Broken at length by the strain of office, Liverpool suffered a stroke in 1827 and died 4 Dec. 1828.

It would be unfair ... to deny that much of the success of Lord Liverpool’s administration was owing to his own prudence, temper, firmness and moderation, and absence of all jealousy, so that on the part of his colleagues, there was a universal acquiescence in his leadership.17

Ref Volumes: 1790-1820

Author: R. G. Thorne

Notes

- 1. Gent. Mag. (1829), i. 81; Leveson Gower, i. 8; Add. 38310, f. 34; 48244, f. 52.

- 2. Leveson Gower, i. 35; Add. 38310, ff. 54, 61, 218; 38566, f. 74; 38567, f. 207; 38580, ff. 27, 31, 39; Geo. III Corresp. i. 740; SRO GD46/17/6, Johnston to Stewart, [8] Mar.; Harewood mss, Canning to Rev. Leigh, 27 Mar.; Public Advertiser, 8, 10 Mar. 1792; Sheridan Letters ed. Price, i. 238.

- 3. Minto, ii. 4; Auckland Jnl., ii. 439.

- 4. Add. 34448, f. 238; 48244, f. 156.

- 5. Add. 33630, f. 24; 51706, Pelham to Lady Holland, 15 Apr.; Sidmouth mss, Mornington to Addington, 3 May; Harewood mss, Canning jnl. 26 Apr., 26, 29 May, 14 June 1794; Canning and his Friends, i. 133.

- 6. Harewood mss, Canning jnl. 16, 18, 29, 31 Dec. 1794; 3, 5, 20, 24 Jan., 5, 21 Feb., 16, 24 Mar.; Canning to Rev. Leigh, 7 Feb. 1795.

- 7. Add. 38310, f. 150; BL 1102.h.12(11).

- 8. SRO GD51/1/200/15; Add. 38310, f. 156.

- 9. Wellesley Pprs. i. 90; Abergavenny mss, Liverpool to Robinson, 9 Feb. 1799.

- 10. C. D. Yonge, Life of 2nd Earl of Liverpool, 39; Add. 38311, f. 68; 48246, f. 105; Glenbervie Diaries, i. 157-8.

- 11. Geo. III Corresp. iii. 2365n; Glenbervie Diaries, i. 205; Colchester, i. 260.

- 12. Glenbervie Diaries i. 179, 221, 269, 295; Malmesbury Diaries, iv. 63; Chatsworth mss, Duchess of Devonshire jnl., 2 Mar.; Malmesbury mss, FitzHarris to Malmesbury, 29 Aug. 1801; PRO 30/8/157, f. 286; Add. 37880, f. 160; 38833, f. 96; HMC Fortescue, vii. 45; Leveson Gower, 309; Colchester, i. 376, 378-381.

- 13. Add. 35702, f. 56; 38236, f. 231; Buckingham, Court and Cabinets, iii. 219, 245; Rose Diaries, i. 464, 467, 510; ii. 489-90; Grey mss, Tierney to Grey, 4 Dec. 1802; Minto, iii. 265.

- 14. Grey mss, Grey to his wife, 24 May 1803; Creevey Pprs. ed. Maxwell, i. 15; Minto, iii. 287; HMC Fortescue, vii. 151; Colchester, i. 421; Add. 38236, f. 258.

- 15. Add. 35714, f. 107; 38236, f. 278; HMC Fortescue, vii. 170; Farington, ii. 105; Lonsdale mss, Ward to Lowther, 14, 20 Nov. 1803.

- 16. Brougham, Hist. Sketches (1839), 293-8; Brydges, Autobiog. i. 181-2.

- 17. Staffs RO, Hatherton diary, 16 Nov. 1844.